In the world of security research, the line between a genuine vulnerability and a false positive can be remarkably thin. A single byte miscalculation, an incorrect assumption about developer intent, or insufficient empirical validation can lead researchers down the wrong path. This article explores a real-world case where initial analysis suggested a critical heap-based off-by-one buffer overflow, but rigorous mathematical validation and empirical testing revealed it to be a false positive. Through this journey, we'll examine the importance of comprehensive validation, the role of static analysis tools, and how even experienced researchers can misinterpret code behavior.

The Initial Discovery

During a security audit of the OpenVAS Scanner codebase, our attention was drawn to the o_krb5_gss_prepare_context() function in misc/openvas-krb5.c. This function is responsible for preparing a Generic Security Services (GSS) context for Kerberos authentication by constructing a target principal string from various components: service name, host name, optional domain, and realm. The code in question appeared straightforward at first glance:

Code Snippet

if (target->domain.len != 0)

{

ALLOCATE_AND_CHECK (target_principal_str, char,

target->host_name.len + target->domain.len

+ target->service.len + creds->realm.len + 4,

result);

sprintf (target_principal_str, "%s/%s/%s@%s",

(char *) target->service.data, (char *) target->host_name.data,

(char *) target->domain.data, (char *) creds->realm.data);

}

else

{

ALLOCATE_AND_CHECK (target_principal_str, char,

target->host_name.len + target->service.len

+ creds->realm.len + 3,

result);

sprintf (target_principal_str, "%s/%s@%s", (char *) target->service.data,

(char *) target->host_name.data, (char *) creds->realm.data);

}

The function constructs a principal string in one of two formats:

service/host_name/domain@realm when a domain is present, or

service/host_name@realm when it's not.

The allocation calculation sums the lengths of all string components and adds a constant value: +4 for the first case and +3 for the second.

The Initial Analysis: A Suspected Vulnerability

Our initial analysis focused on understanding what these constant values represented. In the first branch, the format string "%s/%s/%s@%s" contains three separator characters: two forward slashes and one at sign. In the second branch, "%s/%s@%s" contains two separators: one forward slash and one at sign.

The critical question emerged: did the +4 and +3 values account for the NUL terminator byte required by C strings? Our initial assessment assumed they did not, reasoning that the constants represented only the separator characters. This interpretation suggested a classic off-by-one error where sprintf() would write the NUL terminator beyond the allocated buffer. To validate this hypothesis, we created a proof-of-concept that mimicked the vulnerable code path:

Code Snippet

if (target->domain.len != 0)

{

ALLOCATE_AND_CHECK (target_principal_str, char,

target->host_name.len + target->domain.len

+ target->service.len + creds->realm.len + 4,

result);

sprintf (target_principal_str, "%s/%s/%s@%s",

(char *) target->service.data, (char *) target->host_name.data,

(char *) target->domain.data, (char *) creds->realm.data);

}

else

{

ALLOCATE_AND_CHECK (target_principal_str, char,

target->host_name.len + target->service.len

+ creds->realm.len + 3,

result);

sprintf (target_principal_str, "%s/%s@%s", (char *) target->service.data,

(char *) target->host_name.data, (char *) creds->realm.data);

}

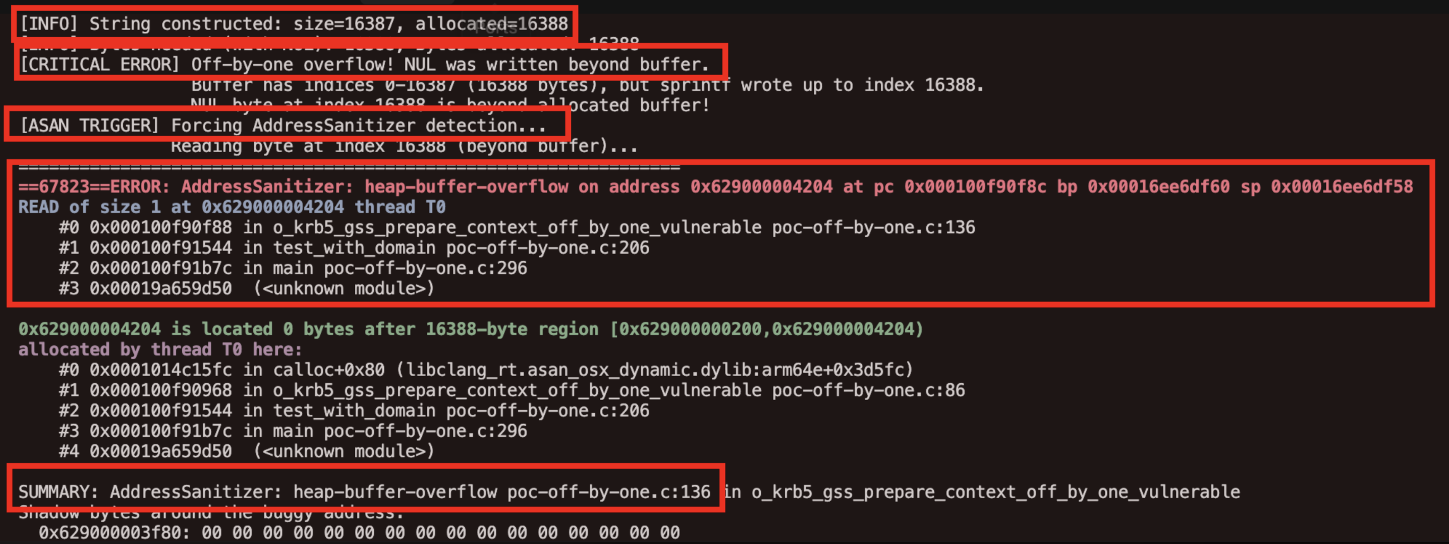

When compiled with AddressSanitizer (ASan) and executed with test strings, this code would trigger ASan warnings when attempting to read or write beyond the allocated buffer. The detection seemed to confirm our suspicion:

The buffer was insufficiently allocated, and operations beyond its bounds would trigger sanitizer alerts.

The Vendor Response: A Different Interpretation

We reported our findings to the OpenVAS security team, expecting confirmation and a coordinated disclosure process. Instead, we received a response that challenged our interpretation entirely. The team explained that their analysis by multiple developers had confirmed there was no vulnerability in their codebase.

Their reasoning was mathematically precise: the +4 in the first branch represented three separator characters plus one NUL terminator byte, not four separator characters. Similarly, the +3 in the second branch represented two separators plus one NUL terminator. In their view, the allocation calculation was correct, and no overflow occurred.

This response forced us to reconsider our analysis. Had we misinterpreted the developer's intent? Was our initial assumption about what the constants represented incorrect? The mathematical consistency of their explanation was undeniable, but we needed empirical validation to be certain.

Mathematical Validation: Breaking Down the Calculation

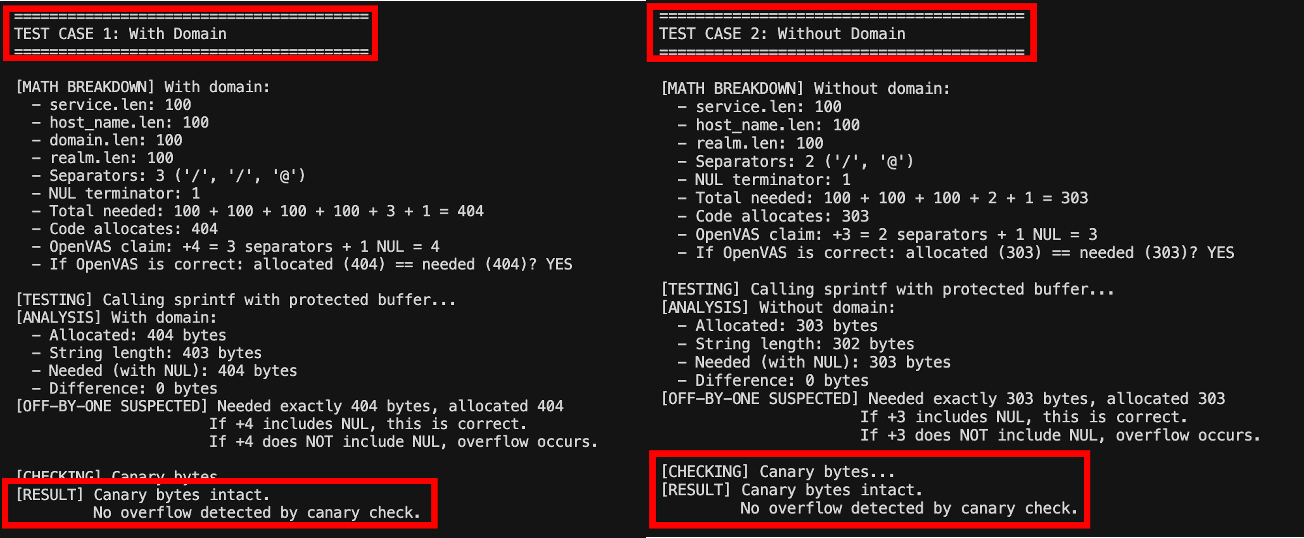

To validate the vendor's claim, we needed to perform a rigorous mathematical analysis of the buffer allocation. Let's examine the first branch in detail, where a domain is present.

The constructed string format is service/host_name/domain@realm. Breaking this down byte by byte, we have: the service string (service.len bytes), a forward slash (1 byte), the host name string (host_name.len bytes), another forward slash (1 byte), the domain string (domain.len bytes), an at sign (1 byte), and the realm string (realm.len bytes). Finally, C strings require a NUL terminator (1 byte).

The total bytes needed equals the sum of all string lengths plus three separator characters plus one NUL terminator: service.len + host_name.len + domain.len + realm.len + 3 + 1, which simplifies to sum(len) + 4.

The code allocates exactly sum(len) + 4 bytes. If the +4 represents 3 separators + 1 NUL, then the allocation is correct. If it represents 4 separators (without NUL), then we have a one-byte under-allocation.

For the second branch, the format is service/host_name@realm. This requires: service string, one forward slash, host name string, one at sign, realm string, and one NUL terminator. The calculation becomes sum(len) + 2 + 1, which equals sum(len) + 3. Again, if +3 represents 2 separators + 1 NUL, the allocation is correct.

The mathematical analysis supported the vendor's interpretation, but mathematics alone cannot prove the absence of a vulnerability. We needed empirical evidence.

Empirical Validation: Building a Definitive Test

To definitively determine whether an overflow occurred, we designed a comprehensive test that would detect any buffer corruption. The test used canary bytes (known values placed before and after the allocated buffer) that would be corrupted if sprintf() wrote beyond the buffer boundaries.

Code Snippet

typedef struct

{

unsigned int canary_before[CANARY_SIZE];

char *buffer;

size_t allocated_size;

unsigned int canary_after[CANARY_SIZE];

} ProtectedBuffer;

ProtectedBuffer *

allocate_protected_buffer (size_t size)

{

ProtectedBuffer *pb = malloc (sizeof (ProtectedBuffer));

if (!pb)

return NULL;

for (int i = 0; i < CANARY_SIZE; i++)

{

pb->canary_before[i] = CANARY_VALUE;

pb->canary_after[i] = CANARY_VALUE;

}

pb->buffer = (char *) calloc (size, sizeof (char));

pb->allocated_size = size;

return pb;

}

After executing sprintf() with the same allocation logic as the original code, we checked whether the canary bytes remained intact:

bool

check_canaries (ProtectedBuffer *pb)

{

for (int i = 0; i < CANARY_SIZE; i++)

{

if (pb->canary_before[i] != CANARY_VALUE)

{

printf ("[OVERFLOW DETECTED] Canary BEFORE buffer corrupted!\n");

return false;

}

if (pb->canary_after[i] != CANARY_VALUE)

{

printf ("[OVERFLOW DETECTED] Canary AFTER buffer corrupted!\n");

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

The test executed sprintf() with various string lengths and checked the canary bytes afterward. In all test cases, the canary bytes remained intact, indicating that sprintf() did not write beyond the allocated buffer boundaries.

AddressSanitizer: A Tool for Detection, Not Proof

Our initial proof-of-concept used AddressSanitizer to detect potential overflows, and it did trigger warnings. However, understanding why ASan triggered is crucial for proper interpretation.

AddressSanitizer works by instrumenting memory accesses and detecting when code reads or writes outside allocated regions. In our initial test, we explicitly attempted to read and write bytes at index allocated_size, which is one byte beyond a buffer of size allocated_size (valid indices are 0 through allocated_size - 1).

The key insight is that ASan detected our test code accessing memory beyond the buffer, not sprintf() itself writing beyond the buffer. When we examined the actual string written by sprintf(), we found that its length matched exactly what would fit in the allocated buffer, including the NUL terminator.

Consider a concrete example: if each component string is 100 bytes, the first branch allocates 100 + 100 + 100 + 100 + 4 = 404 bytes. The constructed string service/host_name/domain@realm has a length of 403 bytes (100+1+100+1+100+1+100), and with the NUL terminator, it requires exactly 404 bytes. The allocation is precisely correct.

When we attempted to read target_principal_str[404] in our test code, ASan correctly flagged this as an out-of-bounds access. However, this was our test code accessing beyond bounds, not sprintf() writing beyond bounds. The sprintf() function wrote the NUL terminator at index 403 (the last valid index), and the string is properly null-terminated within the allocated buffer.

The False Positive: Understanding What Went Wrong

Our initial analysis made a critical assumption: that the constants +4 and +3 represented only separator characters, excluding the NUL terminator. This assumption seemed reasonable given the number of separators in each format string, but it was incorrect.

The developer's intent, as explained by the vendor team, was to include the NUL terminator in these constants. Without explicit comments in the code or access to the original developer's notes, we had no way to know this intent definitively. However, the mathematical consistency of the vendor's explanation, combined with our empirical testing, confirmed their interpretation.

The AddressSanitizer warnings in our initial proof-of-concept were misleading because they detected our test code's out-of-bounds accesses, not actual buffer overflows from sprintf(). This highlights an important principle: sanitizer tools are excellent for detecting memory safety issues, but their output must be interpreted carefully in the context of the actual code behavior, not just test code behavior.

Lessons Learned: The Importance of Rigorous Validation

This case study illustrates several critical principles for security researchers. First, mathematical analysis alone is insufficient; empirical validation through comprehensive testing is essential. Our canary byte test provided definitive evidence that no overflow occurred, regardless of the mathematical interpretation.

Second, static analysis tools and sanitizers are powerful aids, but they require careful interpretation. AddressSanitizer correctly identified out-of-bounds accesses in our test code, but those accesses were artifacts of our testing methodology, not evidence of a vulnerability in the original code.

Third, assumptions about developer intent can lead researchers astray. Without explicit documentation, we assumed the constants represented only separators. The vendor's explanation that they included the NUL terminator was mathematically consistent and empirically validated, but we had no way to know this without their input.

Fourth, comprehensive testing across multiple scenarios is crucial. Our definitive test used canary bytes, mathematical verification, and multiple string length combinations to ensure we weren't missing edge cases. This multi-layered approach provided confidence in our conclusion.

Finally, vendor engagement is valuable even when initial reports are incorrect. The OpenVAS team's detailed mathematical explanation helped us understand our error and refine our testing methodology. This collaborative approach, rather than adversarial disclosure, benefits the entire security community.

Conclusion: The Path to Accurate Vulnerability Assessment

The journey from initial vulnerability report to confirmed false positive demonstrates the complexity of security research. What appeared to be a clear-cut off-by-one buffer overflow required mathematical validation, empirical testing with canary bytes, careful interpretation of sanitizer output, and vendor collaboration to resolve definitively.

The OpenVAS code is correct as written. The +4 and +3 constants do include the NUL terminator byte, and no buffer overflow occurs. Our initial analysis, while methodical, made an incorrect assumption about developer intent that led us down the wrong path.

This case underscores a fundamental truth in security research: the difference between a vulnerability and a false positive often lies in the details. Rigorous validation through multiple testing methodologies, careful interpretation of tool output, and open communication with vendors are all essential components of accurate vulnerability assessment. As security researchers, our goal is not just to find vulnerabilities, but to find real vulnerabilities, and that requires the discipline to validate our findings thoroughly before reporting them.